CHAUVIN : Full-scale opera

Music by Malcolm Hill, Libretto by John Deethardt

THE COMPOSER

Malcolm J. Hill is a resident of Bath, England. By the age of 25, he had amassed a total of 25 degrees, diplomas and prizes. He studied in Holland and Sweden, where he is known as a concert improviser, and at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where he taught music aesthetics and post-graduate composition (full time) for 26 years. He left the Royal Academy in 1995 to devote more time to writing and composing, but continued as a part-time supervisor of post-graduate composition and musicology at London University for five years. He now supervises a few post-doctoral students and is musical director of Bath Chamber Opera. He has composed many works, ranging from solo flute to opera, which have been featured by groups such as Double Image and HEOS, and performed in London’s South Bank halls. Much of his style is of the “lyrical and non-system” type, and around 80% of his compositions are text-related.

THE LIBRETTIST

John F. Deethardt Jr. is a resident of Highlands Ranch (Littleton) Colorado. He is a 1989 professor emeritus of communication studies at Texas Tech University. His doctorate (1967) and M.A. (1964) studies in communication were at Northwestern University; with a bachelor’s degree (1951) and post-graduate work at Indiana University in comparative literature and German. He directed and acted in community and secondary school theatre. He taught eight years in the secondary schools and 26 years at the college and university level. He published articles and book chapters in scholarly publications of communication and futurist associations and the social and behavioural sciences. He believes his libretto has a lyrical quality that readers would find compelling.

COLLABORATION

John Deethardt and Malcolm Hill met on the internet after the outline and much of the first third of the opera’s libretto had been written. After several emails and postal transmissions, they started to collaborate on the whole project. When most of the libretto had been produced, they met in Bath for a few days, mostly to discuss stage-actions and nuances of the last act’s plot. With this exception, all their communication was via email. This correspondence, detailing how the work progressed using email, is now being edited by John Deethardt as a separate booklet which could accompany performances.

It was agreed from the outset that the musical style would be accessible to the average opera-goer, and that the text would remain in English, with only French names given their European pronunciation. The whole opera would last about 145-150 minutes plus intervals between the three acts. Act Two changes from early morning to mid-day, so the work was organized so that this change could either take place during a vocal ensemble or just by lowering the curtain, omitting the ensemble, and raising the curtain to a brighter-lit stage.

What eventually became the agreed libretto balances a predominantly male-singers first act with a female-singers ending to the opera. Because of the changes of setting and personnel between each act, many of the singers’ roles were organized so that non-principal singers could take on a different role in different acts. The opera is through-composed, with each character assigned its own peculiarities; but this does not preclude most soloists being given either a whole aria or at least a partial aria in each act.

SYNOPSIS

Each of the three acts is a single scene, requiring three sets in all.

Nicolas Chauvin, of “chauvinism” notoriety, returns from Waterloo to receive honours from Napoleon, whose charisma engenders a personified alter-ego in Chauvin. Chauvin returns home. His family welcomes him, but he cannot put his experiences in the Napoleonic wars behind him, nor escape the nagging of his alter-ego, and suffers a conflict between his domestic role and his sense of an ideological mission.

He travels around France, carrying his monomania everywhere. At a theatre in Paris he interrupts a play with his ranting, but he still suffers from irresolution. Finally, his alter-ego subsumes his domestic self. In his new incarnation, he abandons the distraught wife to march into the future without them.

THE STORY

A wounded soldier, Nicolas Chauvin, is discharged from Napoleon’s army with high honours. A rogue soldier, Dibroc, is pardoned by Napoleon so that he can assist Chauvin in his return home. From the solicitude of Napoleon toward Chauvin is born, like Athena from the brain of Zeus, fully grown and fully armed, a new Chauvin, IChauvin, representing the thoughtful Chauvin, the incipient ideology of “Chauvinism”.

Chauvin, with Dibroc, arrives home with two comrades, Picot and Souvan. Chauvin’s wife, Adele, and the two children by Nicolas, Henri and Jeanette, welcome him, but he cannot escape his experience of war in the Napoleonic army, nor his alter ego in IChauvin. Napoleon, fleeing from the advancing Allied armies and those who will restore the monarchy, comes through Rochefort, Chauvin’s hometown and birthplace, and happens to stop for a brief respite outside Chauvin’s house where Chauvin’s wife has a bakery. Chauvin recognizes the furtive Napoleon, but he is not accustomed to seeing this divine emperor in his deposed state. He acts brashly and almost gets the emperor captured by some royalist-terrorists before Napoleon makes his escape. Chauvin concludes he must abandon his wife and children and pursue his transcendental view of reality elsewhere.

He will travel around France carrying his ideology to every corner. Chauvin, a true believer, has a natural affinity for a theatrical setting to exhibit his sentiments. At a theatre in Paris he interrupts a play in progress with his ranting. One patron, Mme Germaine de Staël, a prominent literary figure of the time, opposes him. He equivocates, suffering from doubt and irresolution. Finally, Chauvin is subsumed by his ideological alter-ego, IChauvin. In his new incarnation, he alienates Adele. IChauvin goes into the world with his followers, leaving a heartsick Adele behind.

REFERENCES:

Will and Ariel Durant, The Age of Napoleon: A History of European Civilization from 1789 to 1815. New York: MJF Books, 1975.

Imbert de Saint-Amand, Marie Louise: The Island of Elbe, and the Hundred Days. Trans. By Elizabeth Gilbert Martin. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899.

Eric Hoffer, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. New York: Time Inc., Book Division, 1963.

- Christopher Herold, Mistress to an Age: A Life of Madame de Staël. New York: Time-Life Books, 1958.

ACT ONE A wounded soldier, Nicolas Chauvin of “chauvinism” notoriety, returns to Paris from Waterloo to receive honours from Napoleon, whose charisma engenders a personified alter-ego in Chauvin. A rogue soldier, Dibroc, is pardoned by Napoleon so that he can assist Chauvin in his return home. From the solicitude of Napoleon towards Chauvin is born, like Athena from the brain of Zeus, fully grown and fully armed, a new Chauvin, IChauvin, representing the thoughtful Chauvin, the incipient ideology of “Chauvinism”.

ACT TWO Chauvin, with Dibroc, arrives home with two comrades, Picot and Souvan. Chauvin’s wife, Adele, and the two children by Nicolas, Henri and Jeanette, welcome him, but he cannot escape his experience of war in the Napoleonic army, nor his alter ego in IChauvin. Napoleon, fleeing from the advancing Allied armies and those who will restore the monarchy, comes through Rochefort, Chauvin’s hometown and birthplace, and happens to stop for a brief respite outside Chauvin’s house where Chauvin’s wife has a bakery. Chauvin recognizes the furtive Napoleon, but he is not accustomed to seeing this divine emperor in his deposed state. He acts brashly and almost gets the emperor captured by some royalist-terrorists before Napoleon makes his escape. Chauvin concludes he must abandon his wife and children and pursue his transcendental view of reality elsewhere.

ACT THREE Chauvin will travel around France carrying his ideology to every corner. A true believer, he has a natural affinity for a theatrical setting to exhibit his sentiments. At a theatre in Paris he interrupts a play in progress with his ranting. One patron, Mme Germaine de Staël, a prominent literary figure of the time, opposes him. He equivocates, suffering from doubt and irresolution. Finally, Chauvin is subsumed by his ideological alter-ego, IChauvin. In his new incarnation, he alienates Adele. IChauvin goes into the world with his followers, leaving a heartsick Adele behind.

INTRODUCTORY NOTES ON CHAUVIN

Nicolas Chauvin, the mythical super-patriot, was declared to have been born in Rochefort, France, and reported to have flourished in the late 18th Century and early 19th Century. He was a French soldier under the First Republic (the French Revolution) and the Empire (the Napoleonic armies). He was reported to have been born circa 1780, enlisted in Napoleon’s army at age 18, fought in numerous campaigns and wounded 17 times. He showed great courage, and being severely wounded and mutilated, he received from Napoleon a sword (a sabre of honour), a red ribbon, and a pension of 200 francs. He nourished a blind idolatry for his hero, Napoleon. His enthusiasm for the emperor and his professions of militant patriotism won for him the ridicule of his comrades and gave rise to the term, “chauvinism”, the eponym for blind and excessive nationalism. The character was developed by Arrago in searching for the etymology of “Chauvinism” for the Dictionnaire de la Conversation 1834. Presently, exaggerated and excessive nationalism has become a modern social phenomenon. It exalts consciousness of nationality to the extent of spreading hatred of minorities and other nations. Hannah Arendt in “Imperialism, Nationalism, Chauvinism,” The Review of Politics, provides an interesting understanding of the concept:

Chauvinism is an almost natural product of the national concept insofar as it springs directly from the old idea of the ‘national mission.’ . . . (A) nation’s mission might be interpreted precisely as bringing its light to other, less fortunate peoples that, for whatever reason, have miraculously been left by history without a national mission. As long as this concept did not develop into the ideology of chauvinism and remained in the rather vague realm of national or even nationalistic pride, it frequently resulted in a high sense of responsibility for the welfare of backward peoples. [p. 457]

Nationalism is associated with militarism, imperialism and racism. Chauvinism may currently be applied to xenophobia, Christian fundamentalism, ethnocentrism, male chauvinism, etc., or for basically any persecution of out-groups by in-groups. If one were culturally astute, one would be politically correct (to equate the two), and, therefore, one would not be a chauvinist. Ultimately, chauvinism is the fanatical attack of the true believer on the government, stirring to life a complacent and even “decadent” society through a leader who knows the process of religiofication to ignite a national virility. Such fanaticism is an important invention, “a miraculous instrument for raising societies and nations from the dead – an instrument of resurrection.” (Hoffer). Chauvin was lampooned frequently on the French stage in the 1830s, as in a play by Eugène Scribe, called Le soldat laboureur (the citation may have been wrong – and one comprehensive list does not contain that title). His first appearance was in a vaudeville, La Cocarde Tricolore, Episode de la guerre d’Alger, by the brothers Cogniard, Charles Théodore and Jean Hippolyte (1831). Chauvin came to typify the cult of military glory that was popular after 1815, among the Veterans of Napoleon’s armies. It is probably the effect of the Napoleonic wars on Napoleon’s soldiers that contributed significance to the concept of “nationalism” and not anything that Napoleon himself said. Throughout the Nineteenth Century, French chauvinists called for the regeneration of the spirit that had electrified the Napoleonic armies. British chauvinism became “jingoism”, and chauvinism and jingoism were matched by “100 percent Americanism”. What conjectures follow presume those simple facts from secondary sources, and of some facts of historical chronology for the post-Napoleonic period, amplified by the creation of a multitude of fictions. For example, we have Chauvin being born July 4, 1776, and being conscripted into the Revolutionary army at 17, in 1793, during the Reign of Terror.

The life of Nicolas Chauvin is the source of the eponym “chauvinism” or “chauvinist”. Central to the theme is the “appearance” of a second, “spiritual” presence of Nicolas Chauvin, becoming the embodiment of an “ideological” Chauvin (denoted thus: IChauvin). The drama issues from the ideology and the “religiofication” (i.e., unifying a people whose existence is threatened by generating a spirit of self-sacrifice to transform the people, normally democratic, into a militant or revolutionary party) of super-patriotism for the France that was known in the Napoleonic period, beginning with the First Republic, the French Revolution, before the Royalist Restoration. In this conception, chauvinists are one type of people who have adapted to one way of life and who are incapable of adapting to a changed state of affairs. Their adaptation precludes adaptability. Their beliefs are scripted and their brains are wired by charismatic leaders, whose power and authority are based on their mere assertions. They are supported by “true-believers” who too readily accept those ideas. The ideology of the leader and followers is the yardstick by which they measure all things. They are people who have lost their niche and in their rigid denial of a changed state of affairs and facts contrary to their ideas are attempting to cope by re-establishing a state in which their niche is restored to its former concordance with the background, in this case, the military glory under “the little corporal”, the spirit of Napoleon’s armies. Their characteristic reaction is ideologically reactionary, but not violent, at first. The roots of chauvinism lie in this one mythical person’s behaviour, around which coagulated a clot of causes of those times. Our times are seeing the continuation of the struggles of nationalism and the further spread of the phenomenon of cults, along with a rising sensitivity to the conflicts among cultural groups, such as the sexes (sexism, “male chauvinist pig”, “female chauvinist sow”) and an expansion of the eponym into new fields of battle (national and religious chauvinisms). In fact, a chauvinism for every demographic category, sex, age, race, blood, religion, nationality, etc., probably exists as a phenomenon in contemporary society.

THEATRICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Each of the three acts is a single scene, requiring three sets in all.

ACT I, Paris, France, The Élysée Palace, June 21, 1815, mid-morning

ACT II, Rochefort, France, a village square, July 3, 1815, early dawn, changing to afternoon

ACT III, Paris, inside Le Théatre de la Porte-Saint-Martin, 16 months later, November, 1816, Saturday evening.

ACT I

TIME: Wednesday, June 21, 1815, three days after Waterloo, mid-morning

SETTING: The Élysée Palace, Paris, Emperor Napoleon’s throne room. SL is the throne, angled, on four-tiered risers. UC is a balcony and railing, overlooking the courtyard below. A grand entrance arch, curtained in front of large doors, is SR, angled.

ACT II

TIME: July 3, 1815, Monday, before light in the early morning. The moon is low, about to disappear (DC), as the first rays of the sun lighten the sky in the east (UC). At a certain time, noted, during the act, time passes into early afternoon. The curtain may be drawn and the quintet omitted at that point in the middle of the act, or not, at the discretion of the producers.

SETTING: In the environs of Rochefort, France, (Chauvin’s birthplace). A square surrounded by the Chauvin home (SR), which is in part a bakery, a stone wall (US), a butcher shop (UL), a dairy store and an inn (DL). Between the butcher shop and the dairy store is a passageway leading off left. SRC is a tree, under which is a bench. The tree has a large trunk, and the leaves and branches hang from the flies so that the shops around the square are not obscured. CS is a well. Mme. Chauvin’s bakery has a Dutch door through which she conducts her trade. Just outside the door US of it is a table and chairs where patrons may sit and visit, eat bread and drink. Throughout the scene, veteran soldiers trickle in and congregate around the table. US running right and left of center is a stone wall. The gate is UC, but it is cut at a right angle to the wall so that the region beyond is masked by the overlapping wall sections.

HISTORICAL NOTE: (From Imbert de Saint-Amand): Monday, July 3. General Beker, always respectful toward the Emperor, told him in the morning that it might be dangerous to delay in this manner [tarrying in Niort], as there was reason to fear the arrival of an English fleet before Rochefort, which would render his Departure for the United States impossible. Napoleon allowed himself to be convinced, and left Niort, but not without regret. A detachment of light cavalry escorted him. Before evening they entered Rochefort. In the town and its environs were a regiment of naval artillery, fifteen hundred National Guards, and nearly three thousand gens d’armes, all of them well disposed toward the Emperor. They protested their devotion to him. He stayed at the Maritime Prefecture and the people gave him just such a welcome as he had received at Niort. Rochefort is one of the towns on whose sanitation Napoleon had expended most money. For many years he had continued the works for drying up the marshes that surround it – the inhabitants of Rochefort were grateful on that account, and not afraid to show it.

ACT III

TIME: A Saturday evening, late November, 1816

SETTING: This is a theatre-within-a-theatre setting. It could be stylized on three trucks: (1) a stage set; (2) an audience set; and (3) a theatre patron-box set. All references to stages and audiences shall follow these designations: Stage 1 (stage1) is the primary theatre stage on which the opera is taking place, and its audience is Audience 1 (audience1). Stage 2 (stage2) is a secondary stage that is on stage1, and the audience for the play within the play is Audience 2 (audience2). The setting on stage1 is mostly a cutaway of the interior of a theatre. DL and DR are small portions of the theatre’s exterior, stone or brick walls, with a ticket window in the DR portion. A kiosk is plastered with the title, etc., of the production now playing, LA MORT DE CÉSAR by M. de Voltaire.

Plastered across the playbill in large flaming letters is the word “REVIVAL” or, in French, “REPRISE”. The star-actors’ names, Talma and Lafon, are also printed there. The name of the theatre (for such a revival) is Le Théatre de la Porte-Saint-Martin. We see the theatre inside from a side view, the stage2 being stage1 left (SL) and the audience2 section being stage1 right (SR). The slightly raked stage2 is angled from ULC to DL and basically showing a wing and drop arrangement. The stage2 is elevated several feet with stairs up from the audience2 section at DSL. The back stage2 areas, UL, are masked with wing curtains, but because of the angle, the audience1 can see actors off stage2. The audience2 section is right of centre (CR) We see only one audience2 section, the one that would be left of the aisle if we were walking into this theatre, so that the down stage1 area is the aisle running DR to DC. There is also an (unseen) aisle US of the audience2. The right-side profiles of the audience2 members are seen. I have not seen the theatres in Paris, but the setting here detailed meets the requirements of this action. Further research might add authentication, but I am undeterred by the dictates of authenticity; although this is my best guess as to what may be authentic.

NOTE 1: The libretto for the opening of Act 3 is taken from La Mort de César: Act 3, Scenes 3 through 8, the final scenes. From: The Works of Voltaire. A Contemporary Version with notes, a Critique & Biography by the Right Honorable John Morley. Notes by Tobias Smollett. Revised and Modernized New Translation by William F. Fleming, and an Introduction by Olive H.G. Leigh. Copyright, 1901. I have cut the dialog of Voltaire’s play substantially. This play might have been revived for its statement about Cæsar as Napoleon, but I do not know if it truly had a revival; it suits my purposes to use it. Napoleon’s censorship of the theatre had been revoked, and more freedom had crept into the theatre. This is now in public domain.

NOTE 2: Cæsar’s death is announced by the offstage blowing of a busine. Voltaire might have been thinking of the “ancient instrument, as yet inedited, among the antiquities of Herculaneum; it is of a very peculiar kind, lately dugout of Pompeia… It is a Trumpet or large tube of bronze, surrounded by seven small pipes of bone or ivory, inserted in as many of metal. These seem all to terminate in one point, and to have been blown through one mouth-piece. The small pipes are all of the same length and diameter, and were probably unisons to each other, and octaves to the great Tube.” (Charles Burney, A General History of Music, 1776, description of Plate VI, No.10 at the end of Book One).

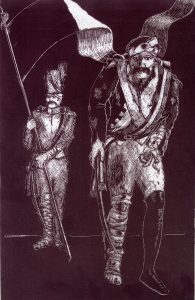

[The picture of the wounded Chauvin, with IChauvin behind him, is by Angela Goodman.]

MAIN SINGLE ROLES

Dramatic Soprano: Adele

Mezzo-soprano: Michelle

Contralto: Mme.de Staël

Countertenor (/Contralto) IChauvin

Baritone: Chauvin

Buffo Bass: Dibroc

Optional DOUBLE and TRIPLE ROLES

Tenor: Napoleon (I and II) = Talma (Antony) (III)

Lyric Tenor: Lucien (I) = Souvan (II and III)

Lyric Tenor: Fouché (I) = Joseph (II) = Caesar (III).

Preferably less lyric in singing quality than the voice for Lucien.

Baritone: Fain (I) = Puiné (II) = Lafon (III)

Bass: Caulincourt (I) = Old Veteran (II) = Brutus (III)

Bass: Bertrand (I) = Picot (II) = First Roman (III)

Loud Bass: Davout (I) = Terrorist Leader (II) = Dolabella (III).

Must be a triple role, not sung by different people.

OTHER SINGLE ROLES

Soprano: Mme Fopin (II) – probably a member of the Chorus.

Jeanette (II) – a child, whose part could be sung offstage.

Henri (II) – a child, whose part could be sung offstage.

Jeanette and Henri could be acted by children (facing away from audience).

CAST PER ACT

ACT I

PRINCIPALS

Adele (sings offstage in Act I), IChauvin, Napoleon, Chauvin, Dibroc.

SUPPORTING CAST

Lucien, Fouché, Baron Fain, Caulincourt, General Bertrand, Davout,

CHORUSES of Ministers, Courtiers and Generals.

Non-singing: Servants, two condemned soldiers, guards.

ACT II

PRINCIPALS

Adele, IChauvin, Napoleon, Chauvin, Dibroc.

SUPPORTING CAST

Fopin, Jeanette, Henri, Michelle, Souvan, Old Veteran,

Picot, Joseph, Puiné, Terrorist Leader

CHORUSES of shoppers, veterans, and White Terrorists

Non-singing: Veterans, guards, shoppers,

ACT III

PRINCIPALS

Adele, IChauvin, Talma (same singer as Napoleon), Chauvin, Dibroc.

SUPPORTING CAST

Michelle, Mme de Staël, Brutus, Caesar, Dolabella, Lafon, First Roman.

CHORUSES of theater actors, audience and veterans.

Non-singing: English guards. Solo female dancer may also be included, ad libitum.

PRINCIPALS CAST

Soprano

Mme Adele Chauvin, four years younger than Chauvin, married him in 1804, at 28 years; in Act I, 35 years of age; a baker whose shop was purchased with Nicolas’ money, obtained through substitute conscription. (Adele represents the realm of the humanistic, natural world, as opposed to the preternatural or supernatural.) Offstage during Act I, on stage most of Acts II and III.

Countertenor (/Contralto)

IChauvin; Chauvin’s ideological manifestation; Chauvin’s fantasy self, whose name becomes the eponym for super patriotism and nationalism; his thoughts. He remains relatively ageless, but could show some slight, increasing maturity, as the ideology grows and takes on a life of its own. (His character represents the supernatural world of the ideological existence of absolute truth.) His part should be sung by a countertenor if of the strident and definitely not fluty vocal quality; otherwise should be sung by a contralto. Top E is quite often required.

Tenor

Napoleon Bonaparte (b. Aug. 15, 1769; general at 24, 1793; d. May 5, 1821,at 51), presently, 46. In Act III, transfers to become Talma: (1763-1826), the most famous classical actor of the time, playing Antony. Talma had early in his career appeared in many of Voltaire’s plays, he was one of the first French actors to appear in classical Roman toga. He was one of the major actors who encouraged Realism; by 1799 his Comédie-Française won the patronage of Napoleon.

Baritone

Nicolas Chauvin (the historical person who has become mythical), a soldier (b. July 4, 1776; the author’s chosen date); at 17 a substitute conscript for a wealthy person in 1793, now, in Act I, 38 years of age, an oft-wounded veteran of 22 years in service; Acts II and III, 39 years of age. [His character copes with the three influences of IChauvin (his transcendental self), the Adele of his natural, humanistic, everyday world, and Dibroc, a preternatural force.] In Act III, Chauvin shows a characteristic, though reversed, pose of Napoleon: his left hand is now tucked inside his coat (across his chest) so that it has hold of the flag for retrieval at will – a trick which he has developed.

Buffo Bass

Antonin Dibroc, one of three soldier-prisoners. (He represents preternatural tendencies.)

MAIN SUPPORTING CAST

Soprano

Henri and Jeanette Henri, 10, son of Nicolas and Adele, conceived during one of Chauvin’s many convalescences, probably around the time when Chauvin was called to stand guard in the cathedral at Napoleon’s coronation in 1805. Jeanette, 8, daughter of Nicolas and Adele. Either or both parts could be sung by children, or acted by children and sung offstage by appropriate voices, the child-actors “singing” with their backs to the audience during the longer arias. Each appears in Act II only.

Mezzo

Michelle Couvé, Adele’s companion, “Aunt” to Adele’s children. In Act II and III.

Contralto

Mme Germaine de Staël. The part calls for clear and rapid diction, rather than putting tonal beauty to the fore. Although she is ailing, her mind is quick and active, and it is these qualities which the voice must demonstrate. Precise pitch, for her, is only important when ensemble-singing. An intellectual rather than emotional manner, where her words can easily be understood as vicious. In Act III only.

NOTE: Her dates are April 22, 1766-July 14, 1817; she lived 51 years, 3 months. In ACT III, 50 years old. Germaine’s health is failing, but her activities know no respite. She is on drugs, suffering stomach disorders and a weakening heart. She will suffer a stroke in three months (February 21, 1817), lie flat for three months, be moved, and then die July 14, 1817. Unable to sleep at night, and not finding enough to hold her interest, she attempts to amuse herself with a night out at the theater with friends and family to see a revival of Voltaire’s play, which in itself is a manifestation of the extremely partisan atmosphere reigning in France at this time. Voltaire (1694-1778) was a friend of Mme. De Staël’s mother, Mme Suzanne Necker. She was also an admirer of Talma. Napoleon considered her an enemy of his, censored her works, and exiled her from France for many years, although she saved him at one point from his enemies toward the end of Napoleon’s regime.

Tenor

Fouché (I) = Joseph (II) = Caesar (III) : Lyric Tenor. Joseph Fouché, Duke of Otranto, was Minister of Police in Act One. Joseph in Act Two is one of Napoleon’s brothers.

Baritone

Baron Fain (I) [Napoleon’s secretary] = Guillaume Puiné (II) [a citizen Bonapartist who was actually killed by terrorists in the manner described in the second act] = Pierre Lafon (III) [tragedian, previously a rival of Talma’s, playing the conspirator, Cassius.]

Bass

Davout (I) = Terrorist Leader (II) = Dolabella (III) : Should all be played by the same singer (even if the other double-castings are not followed). A loud, bombastic style, with more attention to portamento and large dynamics rather than pure pitch. Louis Davout is Minister of War in Act 1.

ADDITIONAL CAST

Soprano

Mme. Fopin, a shopper in Act II (could easily be a Chorus-member)

Terrorist (II) one of the quintet, here able to sound raucous (elsewhere in the opera, could be a Chorus-member).

Mezzo

Terrorist (II) one of the quintet, here able to sound raucous (elsewhere in the opera, could be a Chorus-member).

Tenor

Lucien (I) = Souvan (II) : Lyric tenor. Lucien was one of Napoleon’s brothers. Souvan is one of the two veterans who accompany Dibroc and Chauvin to Rochefort. As such, he is in the audience for the play in (III), but only sings as a member of Chauvin’s followers during (III).

Terrorist (II) one of the quintet, here able to sound raucous (elsewhere in the opera, could be a Chorus-member).

Baritone

Terrorist (II) one of the quintet, here able to sound raucous (elsewhere in the opera, could be a Chorus-member).

Bass Baritone

Caulincourt (I) [long-time friend of Napoleon] = Old Veteran (II) = Brutus (III)

Bass

General Bertrand (I) = Picot (II) [and (III) or = First Roman (III)]. Picot is one of the two companions with whom Chauvin and Dibroc journey to Rochefort. If Picot is in the play’s audience and like Souvan sings only as a member of Chauvin’s followers, then the First Roman one-line part could be sung by a member of the actor’s chorus.

Dancer

In Act Three, there is an extended aria (sung by IChauvin) – a fast, veiled waltz – which could be accompanied by a female dancer, dressed in the French tricolor. The dancer could move around the whole stage or be back-projected onto the back-wall scenery; or just be omitted.

CHORUSES

ACT I

CHORUS OF MINISTERS, including Joseph Fouché, Duke of Otranto, Minister of Police; and Louis Davout, Minister of War. The ministers are all taller than Napoleon; in his presence, they stoop down, minimizing their height.

CHORUS OF COURTIERS, including Caulaincourt, Napoleon’s long-time companion; Colonel Planat, Napoleon’s aide-de-camp; Marchand, Napoleon’s valet; aides and secretaries. Ladies of the court stand in the background. The taller courtiers minimize their height in the presence of the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, emphasizing a toadying posture.

CHORUS OF GENERALS, including Bertrand, and other officers. The officers make no attempt to “minimize” themselves in the presence of the general, not so much toadying as showing normal respect.

ACT II

CHORUSES OF SHOPPERS, VETERANS, TERRORISTS

ACT III

CHORUSES OF AUDIENCE-MEMBERS, VETERANS, ACTORS (Romans).

In Act III, the CHORUSES OF THEATRE PATRONS are constituted as follows:

Talma’s (Antony/Talma’s) claque, favored by Chauvin

Lafon’s (Cassius/Lafon’s) claque, favored by Mme De Staël

Allied soldiers, from England

Other theatre patrons in the audience2 section

In the early part of Act III, the ladies of the chorus sing expressively; but after the subsuming of Chauvin, they assume the role of the Ancient Greek Chorus, commenting on the actions, without any vocal passion.

DURATION

Act One 49 minutes

Act Two 51 minutes (the empty stage section starts after 37 minutes)

Act Three 48 minutes

THE ORCHESTRA

The minimum orchestra needed:

Piccolo

2 Flutes

2 Oboes

2 Clarinets in A (the second doubling Clarinet in E flat)

Bass Clarinet

Bassoon

Contra-bassoon

4 Horns

3 Trumpets

2 Tenor Trombones

Bass Trombone

Tuba in F

Timpani

3 percussion players

Celesta

Harp

A large number of strings

Percussion includes the following:

Glockenspiel [player 1], Xylophone [player 2], Vibraphone [player 3],

2 gongs (pitched C and D if possible),

2 snare drums, tenor drum, bass drum, ratchet,

4 temple blocks, suspended cymbals, crash cymbals,

tam-tam, 2 rifle-shots